Stanley Kubrick had a very distinctive creative process that he carried throughout all of his films. He would patiently wait for a new trend or genre to emerge and would then contemplate the aspects of the movement. He sought to distill the group of films down to their essence and to tease out out the underlying philosophies inherent within them. Kubrick would then arguably make the best film of the genre. With "2001: A Space Odyssey," Kubrick not only made the best and most influential science fiction film to date, he made what I think is the greatest and most important film in the history of the art form.

Like many other Kubrick films, "2001" presents some challenges to viewing. In its running time of 160 minutes, only 20 or so have any speaking. The rest of the film includes powerful images that are intended to inspire contemplation and awe. Because the film has a large plot that encompasses all of human evolution, and because it has a nontraditional method of storytelling, it's easy for some to dismiss the film as too vague or even boring. Ironically, I think "2001" is a very precise film from a director who is famous for being insanely detailed. In this review, I would like to present my own interpretation of the film. My following thoughts must come with a disclaimer that any piece of true art will be open to multiple interpretations. My opinions should not prevent anyone from disagreeing or forming their own views. Debate, I think, more than anything, was Kubrick's intention.

The film opens with a long musical prologue, which I believe represents the creation of simple organisms in the sea from the primordial material on earth. We then see multiple, motionless images of the African savanna without any land animals or ancestors of human beings. These few images help us grasp the concept that the earth is much older than us and our time span has been short compared to the long timeline of earth's existence.

As the images continue, we are shown various animals and a group of timid apes competing with other animals to eat grass. Surrounded by dangerous carnivores, the apes are in constant peril. Their environment demanded an evolutionary leap for their own survival. One night, as the cowering apes huddled together for warmth and protection, one of the them, who is called Moongazer in the credits, stands up to see a giant black monolith pointing to the moon. The other apes follow and are fascinated by a formation that seems artificially placed there. In Arthur C. Clarke's original book, the monoliths were placed by alien lifeforms, but in Kubrick's version, the source of the monolith is left a mystery and up to interpretation. The polished black monolith symbolizes an evolutionary epiphany, that the apes could manipulate their environment with tools. The smooth monolith was not a product of nature. In fact, it stands in stark contrast to its surroundings. It is instead a creation using higher intelligence. Tools will make possible the next evolutionary jump for the primitive apes, which will culminate in their dominance of earth and their departure into the cosmos.

But how do primitive apes "find" or "discover" tools? Kubrick has an ingenious scene showing that discovering actually means repurposing. Challenged by an evolutionary need, Moongazer comes upon an animal carcass. It plays around with rib bones and starts using one of them as a hammer. This scene is made even more wonderful by the use of Richard Strauss' "Also Spach Zarathustra," showing the power and grandeur of discovery. At that moment, the ape becomes a human being, at least in trajectory.

The discovery of tools gives rise to the central theme of the film: that technology can be used for both life and death. As for life, tools make it possible for the apes to hunt animals and obtain meat protein, the resource responsible for the growth of the human brain in the next epoch. Tools can also be a form of protection from other predators. But what gives life to emerging human beings also brings death. In the next scene, the apes have separated into hunting tribes and use the tools to battle each other for control over resources, in this case, a watering hole. Moongazer beats another to death and establishes dominance and control. This theme of tools and their connection to life and death will repeat throughout the entire movie. From the beginning, man has sowed the seeds of his own destruction through technology, an important message to keep in mind during the film's release during the cold war and the era of mutually assured destruction.

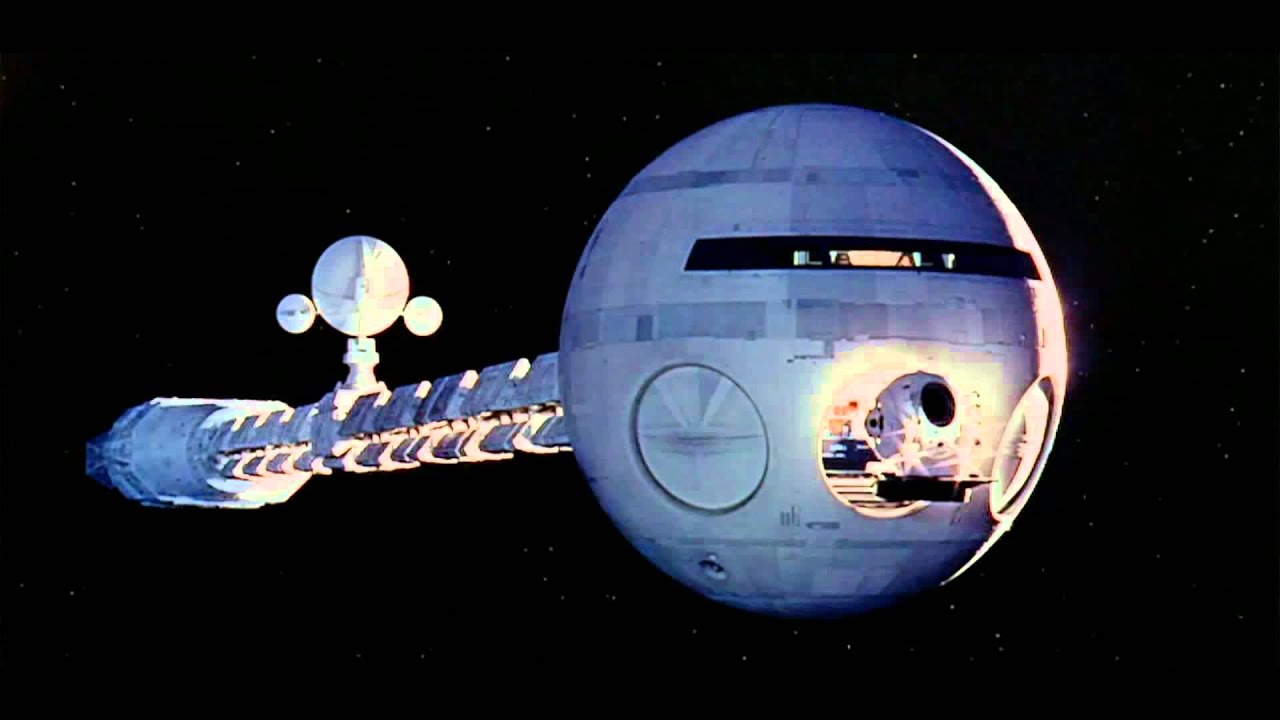

In what has been called the biggest jump cut in film history, Moongazer throws his bone weapon into the air and it instantaneously becomes a space satellite. The scene places us in the year 2001 after hundreds of thousands of years of human evolution. Our tools have become quite complicated and impressive. Kubrick encompasses the beauty and symmetry of civilization with Strauss' "Blue Danube Waltz." Just as classical music demonstrates a high amount of orchestration and precision, we see beautiful spacecrafts floating elegantly with similar perfect synchronization. Kubrick shows how much science and mathematics have allowed us to coordinate amazingly complicated feats like flying into space and docking ships in zero gravity. What is clear in Arthur C. Clarke's book, but not so much in the film, is that the satellite that morphs from the ape's bone is actually a bomb. Again, technology for both life and death.

The special effects, which later earned Kubrick his only Oscar, are amazing. The models, back lit set pieces, and camera work make everything look incredibly real. It is humbling to see that Kubrick's effects have not been topped by even CGI graphics. It is worth mentioning that Kubrick made "2001" before anyone knew what earth looked like from space and how objects would act in zero gravity. Everything moves in circular motion not only to show the harmony and beauty of movement but also because scientists believed that ships would have to move with centrifugal force to instill gravity for astronauts.

One significant problem that Kubrick solved was how to film "space." Indeed, how does one show the vastness and sometimes nothingness of space? His method of including smaller objects next to larger ones helped give scale, which was invaluable to the look of the movie. All future movies set in space, including the Star Wars, Alien, and Star Trek franchises mimic Kubrick's techniques. Part of this film's greatness is the fact that it influenced so many other films that would come to define movie history.

On the Pan Am commercial spaceship, we are introduced to a scientist who is embarking on a trip to a space station and then to the moon for official government business. A few visual images key us into more of Kubrick's themes: the passengers on board are eating meals that closely resemble baby food; the stewardess has difficulty walking in zero gravity and stumbles around like a toddler learning to walk; finally, a pen slips away from the sleeping passenger and floats away until the stewardess returns it to his pocket. All of these aspects symbolize man entering a nascent stage of space travel. Additionally, these images point to how unnatural space travel is. Human beings are essentially infants outside of earth, drawing comparisons to the weakness of apes in their nascence before they developed proper tools.

The scientist disembarks from the ship and learns that there is a serious epidemic on the moon base. He prepares for a briefing but then finds out that the epidemic story was actually a decoy to cover the fact that workers have found a black monolith on the moon. In a theme that will come full circle later in the film, deception is a tool developed by human beings that brings both life and death. In this case, the lie was an effort to forestall panic.

The scientist and his team take a spaceship to the moon in order to inspect the monolith. Once again, Kubrick provides an array of amazing, beautiful images that look astoundingly real. These set pieces look so real, in fact, that many have implicated Kubrick in a conspiracy to fake the moon landing using his prowess exhibited in "2001." As the scientists arrive at the monolith, they approach it in much the same way as the apes and notice that it is pointing to Jupiter. Challenged this time with curiosity for discovery, the humans are driven towards the unknown.

The movie picks up on a ship destined for Jupiter. One could argue that the ship resembles a sperm, once again demonstrating the infancy of humans in space. Several scientists are on board; some are awake while others are in extended hibernation. We are also introduced to one of the greatest film villains of all time: the HAL 9000 computer, which is designed to be the perfect, most advanced tool ever devised by human beings. In fact, HAL is such an advanced tool that he essentially becomes a cognizant human being with critical thinking skills and emotions. He runs the entire ship and maintains a cordial friendship with the astronauts. One of the aspects of this section that I love is how the astronauts, after hundreds of thousands of years of evolution, resemble a collected, almost emotionless computer-like being, while HAL, who just became operational a few days ago, acts like an insecure, neurotic character from a Woody Allen film. Humans have learned to control their emotions and instead depend on reason. HAL, at the beginning of his evolution, is overtly instinctual and emotional.

HAL confides in the astronauts that he is anxious about the mission and reports that the ship's radio transmitter has been malfunctioning and needs to be replaced. The astronauts suit up, go outside the ship, and check the radio. It is worth noting how Kubrick emphasizes the deep breathing of the astronaut in the space suit, pointing out again how unnatural it is for humans to be in space. After the radio is found to be completely operational, the astronauts question HAL's capability to function correctly, and discuss the possibility of shutting him down. They do this in secret away from HAL's knowledge by turning off audio communication. Amusingly, HAL is able to read their lips and catch on to their plan. He hatches his own plot to lure one of the astronauts outside of the ship by destroying the radio and then attacking him with a satellite spaceship. He also knows that Bowman, the other astronaut, will come to his partner's rescue and will be eventually locked out as well. HAL also kills all of the astronauts in hibernation. So much for putting the computer in charge of everything.

What is truly amazing about this sequence is how HAL exhibits attributes of a lowly evolved human being (he became operational just a few days prior). After his ascension into basic consciousness, HALS's first concern is to fear for his own survival, just as the lowly evolved apes did. He then uses the modern tool of deception to kill the astronauts. As a sentient human like machine, HAL's first impulse was to kill. At this point, Kubrick really starts to bring home his theme about how our elegant civilization is belied by primitive ape-like instincts to survive at the cost of other beings.

While HAL's plan is immediately successful, he doesn't count on Bowman's ability to innovate and adapt. Importantly, Bowman takes control of his emotions, a sign of his higher evolution, and works out a way to reenter the ship using the manual lock. Bowman reenters the ship and immediately goes to disconnect HAL for his own survival. But if HAL is a conscious, sentient being, is Bowman murdering him? As HAL pleads for his life and expresses fear at the loss of his consciousness, Bowman disconnects HAL in a slow methodical way, piece by piece. Compare Bowman's slow, subtle murder of HAL to the ape in the beginning of the film who violently beats an enemy over the head with a bone. The former may seem more civilized and technical, but it's still murder nonetheless.

After HAL is terminated, a television screen begins informing Bowman that the mission to Jupiter was to retrieve another monolith floating near the planet's atmosphere. Again, this formation represents an evolutionary challenge to the next level. Bowman chases the monolith and from the audience's perspective, the floating monolith turns horizontal and becomes the movie screen. We, the audience, now become part of the experience and the transformation as we go with Bowman through a stargate. This stunning sequence, wholly new to film, was achieved by shooting lasers straight into the camera lens.

But what is the next evolutionary step that we are to take with Bowman? What are we challenged to do? Throughout the film, we continually saw how, in one sense, evolution was based on the creation of tools, which, in turn, gave rise to civilization. While "2001: A Space Odyssey" certainly celebrates the ingenuity of man and his curiosity to explore the cosmos, Kubrick used the film to make the statement to a proud American nation that technological innovation is not necessarily progress. While we have come a long way from primitive apes and bone tools, we still have not evolved past our primitive instincts to kill and conduct war. Our tools are infinitely more complicated and impressive, but we use them for the same bipolar purpose as our primitive ancestors did: life and death. Our advanced spaceship is the primitive ape's bone.

Our next evolutionary challenge is to overcome our primitive instincts and emotions and to live peacefully under pure reason. That is the future. As we pass with Bowman through the stargate, we can see images of earth but in a different, almost psychedelic perspective. Kubrick used filmmaking to give us an experience that will change our perspective on our place in the universe and our direction as a species. See the big picture, not the petty need for violence and destruction.

At the end of the stargate, Bowman finds himself in a fancy room, presumably some sort of artificial alien habitat for observation. He watches himself age slowly (maybe even evolve slowly). At one point, he knocks a wine glass off a table and sees that the wine is still intact despite the fact that the container is destroyed. This foreshadows Bowman's bodily death and ascension into the spiritual world. As Bowman is lying on his deathbed, he reaches up to another monolith, dies, and transforms into what Arthur C. Clarke called "the star child," a being that can see the world anew.

While human beings and their ancestors shared some primitive attributes including the penchant for killing in a life-death cycle, there is one common attribute that defined us from the very beginning: a sense of bold curiosity, wonder, and the need to discover. This characteristic has driven both our ancestors and modern humans up the food chain, to the moon, and beyond the stars. "2001: A Space Odyssey" is the only film I've seen that attempts to be an experience rather than passive entertainment. It wants you to see the journey of human beings in the universe, a feat only made possible by the medium of film. Kubrick is not really interested in entertaining us as much as he is in inspiring our awe and wonder, the defining characteristic that makes us human and drives us to greater and greater heights.

No comments:

Post a Comment