Friday, January 22, 2016

The Passion of the Christ

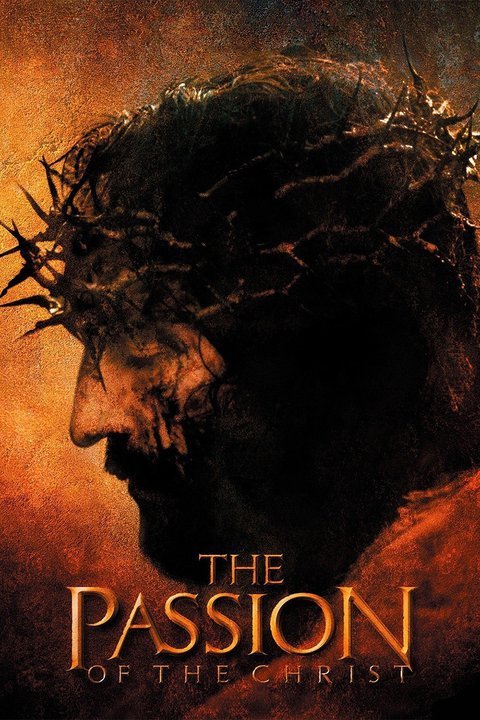

The question surrounding "The Passion of the Christ" is not how well it is made, but why it had to be made in the first place. There is no denying that Mel Gibson is a talented filmmaker. If Gibson's goal was simply to portray the depth of Jesus's suffering, then he made a perfect film. From the opening scene in the Garden of Gethsemane, it grabs hold of your attention and doesn't let go until the end. Moreover, Jim Cavieziel's performance as Jesus is truly amazing. Given his devout faith, he gives a very heartfelt depiction, one of the best ever put on film.

Ironically, the reason why this film is so good also raises troubling questions about the necessity of making a movie about the passion narrative. "The Passion of the Christ" bears strikingly resemblance to all of Gibson's other successful films, all of which glorify suffering and violence to the highest degree possible for a mainstream film. Whether in "Braveheart," "Apocalypto" or "Payback," each of Gibson's protagonists endures everything from disembowelment, decapitation, defenestration (my favorite word---we actually needed a verb to describe pushing someone out of a window) to the untimely death of a child. Additionally, many of Gibson's films have an occupying power with its proverbial boot on the neck of a population seeking freedom or atonement. The English in "Braveheart" are interchangeable with the Romans, and to a lesser extent, the Sanhedrin, in "The Passion." Gibson likes his barbarism and civilization stories, and sometimes questions who the real barbarians are.

The problem with borrowing these common themes, particularly the obsession with violence, from Gibson's other movies is that it actually detracts from the importance of Jesus's suffering. Is Jesus just another William Wallace yelling in defiance at the hour of his death? Does Jesus's story warrant more than Wallace's silly, cartoonish death in which he yells "Freedom" despite having the contents of his intrathoracic cavity ripped out? Certainly, Jesus had a bigger impact on the world than William Wallace did and deserved a death with the full story and power behind it. But we never get to see that.

The other problem with adding Gibson's barbarism versus civilization trope is that it continues to single out the Jews (used nefariously as a generalized group) as the people who are solely responsible for Jesus's death. Not only is this somewhat historically inaccurate, but it has led to a millennia of antisemitism throughout the world. Gibson, who has a preexisting penchant for being over the top, made it very clear who the enemies of Jesus were. Jewish high priests in the film have exaggerated features, most noticeably rotted teeth, cracked lips, and cruel looking faces. In reality, the responsibility for Jesus's death lies just as much at the feet of the Romans as it does the Sanhedrin. The difference is that the Romans look nice and pretty in Gibson's film. Interestingly, against the grain of historical knowledge, Gibson portrays Pontius Pilate in a most sympathetic manner. He is the leader of an occupying force in a barbaric land. As the story goes, he finds nothing wrong with Jesus and even tries to save his life by offering to execute Barrabas, a violent murderer, in his stead. The Jewish leaders refuse and Pilate famously washes his hands of Jesus and allows (not orders) his crucifixion.

Yet, the actual history of Jesus's death is far more interesting. Jesus was a Jewish nationalist who spoke against the Roman occupation of Palestine and wanted to return the territory to Jewish home rule. This goal not only entailed protesting against the Romans, but also Jewish leaders in the Sanhedrin who continued to cooperate with the occupation and quell protest. In other words, Jesus had two enemies: the Romans and the Jewish high priests, both of whom would eventually kill him to quiet his insurrection. Throughout his life, Jesus's actions and messages centered around rejecting the legitimacy of Roman rule and the cooperative Jewish authorities who ruled the temple with overbearing rules and taxation. Jesus repeated actions and phrases which rejected both authorities: he "cured" lepers and the unclean and told them to enter the temple in clear violation of the rules; he overturned the tables of monied interests in the temple and set the sacrificial animals, which were to be taxed, out of their pens; he recruited working class fisherman on the coast and paraded into Jerusalem under the shades of palms, proclaiming his own power and rejecting that of the Roman-Sanhedrin complex; finally, he spoke about uprooting the social structure, preaching that the first would be last and the last would be first. Jesus's rejection of the Jewish high priest aristocracy was key to Jewish independence.

In reality, given his reputation for killing a plethora of previous messiahs, Pilate would have been more than happy to crucify Jesus, as he would any other Jewish upstart who created disorder. When the Romans hung the sign on Jesus's cross informing the crowd that he was "King of the Jews," this was not an ironic statement, but a clear charge of the ROMAN law Jesus had violated. He had rejected the established order of the Sanhedrin over the Jewish populace and sought to inspire revolution against the Romans. Pilate did not have to think twice about sentencing Jesus. As a small aside, the reason why Pilate is later exonerated from the responsibility of killing Jesus in the gospels is because those holy works were written at least a century later, during a time when Jews were trying to bury the proverbial hatchet with Roman rule. Blaming Pilate would incite too many Jews against the Romans in a time when peace was needed. In sum, Gibson actually missed a good opportunity to expound on his hatred of occupying powers and clear devotion for tribes fighting for independence.

But the final question is why Gibson thought making a film centering on the graphic suffering and death of Jesus or any human being was worth making. As I said above, the passion narrative has its roots in antisemitism throughout world history. But even more, I think focusing on Jesus's death in gory detail detracts from the entire story of Jesus, which is filled with teachings that say more about the nature of his ministry than his death ever could. Growing up Catholic, I am familiar with the concept that Jesus's death is the primary mechanism by which humanity's sins were forgiven and life everlasting made possible. Nonetheless, Jesus's death and subsequent resurrection were relatively unimportant in the first few decades of the Christian church. Jesus's power came from his message of Jewish nationalism. It was not until later that St. Paul changed the focus of the ministry to be more universal to disparate areas in the Roman Empire. This is the point, later in the game, when the stories of resurrection came into the picture---when the church needed to lift Jesus's status to outsiders. Jesus had been humiliated, crucified, and killed---his story was in desperate need of a plot device to restore his reputation among skeptics. After all, you can't have a messiah if he's dead and in ill repute.

The main point is that Jesus's death and resurrection only has meaning in the shadow of the rest of his life and ministry. It was his message of Jewish collaboration and shared protest against the occupiers and the Sanhedrin that led to his death. All of the sublime statements we remember Jesus saying about love, forgiveness, and social acceptance were said well before his death. Without those teachings and the subsequent writings of the early church, Jesus was just another would-be messiah (and there were hundreds of them) who was killed after he stirred up enough trouble.

"The Passion of the Christ" has some missed opportunities and goes overboard with the violence. Gallons upon gallons of blood are spilled in this film, and the kicks, punches, and torture are delivered liberally. I am not too keen on snuff and torture films---especially when they exist outside a larger story. Yet, it is a strikingly well acted and directed film that deserves some appreciation. In the end, they say the book is always better than the movie. Perhaps a dusting off the bible is in order.

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

No comments:

Post a Comment